At 8 pm last Tuesday, the same day as the US election, the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, made a televised address to the nation. Though this public address was an unusual event for Modi, the broadcast was not widely publicized, as apparently is the norm for PM speeches in India. But if people weren’t paying attention then, they are now.

About halfway through his remarks, Modi made a bombshell announcement. He declared that at the stroke of midnight on Wednesday–four hours from the moment of his speech–all 500 and 1000 rupee notes would cease to have any value in India. As Modi put it, these notes ”would become waste paper.”

To put this in context, a 1000 rupee note is worth approximately $15 USD at today’s exchange rate, a 500 rupee note half that. Because many (most?) Indian merchants and businesses do not accept credit cards, and very few Indians hold such cards, Rs 1000 and 500 notes were, until last Wednesday, used in hundreds of millions of transactions by India’s one billion person populace each day. Given this fact, Modi acknowledged the problems his abrupt cash cancellation would likely cause. But he deemed it a necessary “surgical strike against black money.”

“Black money” refers to the huge amount of unaccounted for cash in the Indian economy–cash that is stockpiled (often in Rs 500 and 1000 denominations) by individuals and businesses rather than deposited in the bank. By one measure, black money accounts for nearly a third of the Indian GDP.

It is widely acknowledged that this black money is used to fund corrupt practices prevalent in India: bribes to government officials in return for political favors, bribes by political candidates in return for votes, bribes made in business in order to “get things done,” bribes that are open and notorious throughout the country. “Black money” also refers to cointerfeit rupee notes that are allegedly imported from Pakistan to fund terrorist activities in India.

Apart from these illicit purposes, it is well recognized that a significant portion of the country’s so-called “black money”–the money Modi declared “waste paper”–is cash that many law-abiding Indian citizens choose to keep at home, under their proverbial mattresses, rather in banks that they don’t completely trust or care to deal with.

For this reason, and as Modi acknowledged, his decision to render all of the country’s Rs 1000 and 500 notes worthless has caused huge headaches and even hardship to the Indian people. Modi provided a brief grace period during which Indian citizens may exchange their worthless notes for newly minted and legitimate Rs 2000 notes or for bulky piles of old Rs 100 notes. But the rush on the banks by the one billion person populace to make these exchanges is enormous. The lines go on endlessly and, from what we’ve seen, the “good” cash available for exchange runs out long before most have had their turn. Mlreovr, there are limits on the amounts that can be exchanged without incurring hefty fines.

Good cash can also be withdrawn by Indian citizens from their bank accounts, but, again, only in limited amounts and only by people who actually have bank accounts. Many Indians, particularly those who are poor or living outside of the cities, have no accounts.

While nothing compared to what the India people are going through, there’s also an effect on the tourists–e.g., us.

At the time of Modi’s announcement, we (like many foreigners) had hundreds of dollars worth of of Rs 1000 and 500s in our pockets. We had withdrawn large amounts because of the large transaction fees charged for each witbdrawal and because of how often we found ourselves unable to use credit cards. We had, by design, planned our time in India to include a fair number of large, Western style hotels, a necessary refuge (esp for the kids) from the fascinating but sometimes overwhelming sounds, sights, and rush of the country. Still, intent on seeing something closer to the real India, we’d also planned to spend time in less urban areas, staying in the homes of Indian families, where we could live, in at least some ways, as these families do.

These “homestays,” unlike ITCs and Le Meridiens, are not accommodations that can be paid for by Visa or Amex. They deal in cash only. And, as luck would have it, we had several of our homestay visits just as the cash supply was getting really tight. Switch back to the credit card friendly hotels, you say? Good idea. But also one had by many other travellers, making the supply of hotel rooms short as well…

I’ll spare you all the details of how we’ve managed this challenge, like how yesterday Brendan and I waited in a hot line in Goa for hours while the kids waited in a taxi, only to have the cash run out when our turn was two people away. What I cannot omit is that things would have been much more difficult without the kindness and trust of the Indian people we’ve met during this time. Like a family who put us up for nothing but a promise that we would wire dollars as soon we could.

Or the mother who fed our whole 6 person crew for essentially nothing, asking only for a good Trip Advisor review and an extra pic with Phoebe in return.

She also let us help cook!

These experiences, and others, make us very glad we stuck with our homestay plan, eschewing the cush ITC life for at least a little while.

What has also impressed us immensely is the patience, optimism, and general good cheer we’ve seen from the India people about the whole situation. These people could complain about Modi’s measure if they wished to. Based on what we’ve read in the paper, the opposition party is doing its best to stir up anger and angst.

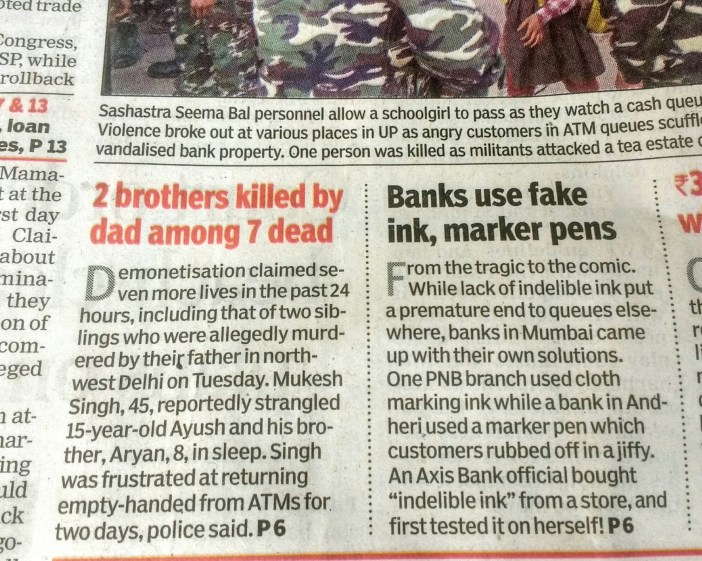

But everyone we’ve asked says the short term hardship to them and their families is worth the long term benefit to the country of cleaning up corruption. Admittedly, our conversations represent a small, anecdotal sample. And today’s papers, a week into the cancellation, indicate that tempers are rising, especially in the cities, with some horrifically tragic results.

There’s also the question of whether Modi’s move will be successful in its goal of reducing corruption (will people just find another way?) or whether the cancellation and all the hardship was necessary to achieve this purpose.

Regardless, we have found it heartening–and sadly a bit foreign to our recent American experience–to hear people so quickly put their short term personal self interest after what they believe is important for the long term good of their country. Though we still have most no cash in hand, nor any leads on well-stocked ATMs, we choose to adopt that patience and optimism as we prepare to head off for a trek in the lower Himalayas (near Darjeeling), after enjoying just a few more sunsets like this on the Arabian Sea.

Wish us luck and, and more importantly, send your good thoughts to India.

This was a great piece – very interesting. Hope you all have a wonderful Thanksgiving. We will miss you!

We will miss you all too! Say hi to everyone for us.